What 'Dog Songs' Tells Us About Love, Loss, and Loyalty

To Mary Oliver, the unleashed dog is a kind of poetry.

Mary Oliver (1935-2019) was a one-of-a-kind nature poet – immensely quotable and soul-stirring. My introduction to her was both sudden and gradual. I knew where her collections sat at my local library, and I'd brush their spines as I passed through. The opening line of her arguably most famous work, "Wild Geese," would pop up in my head sporadically – a reminder to soften my gaze and my inner critic.

Yet, my more in-depth acquaintance with her work came when I took home my late grandfather's book collection. He owned a lot of Mary Oliver's books, though I'd never heard him talk about her work.

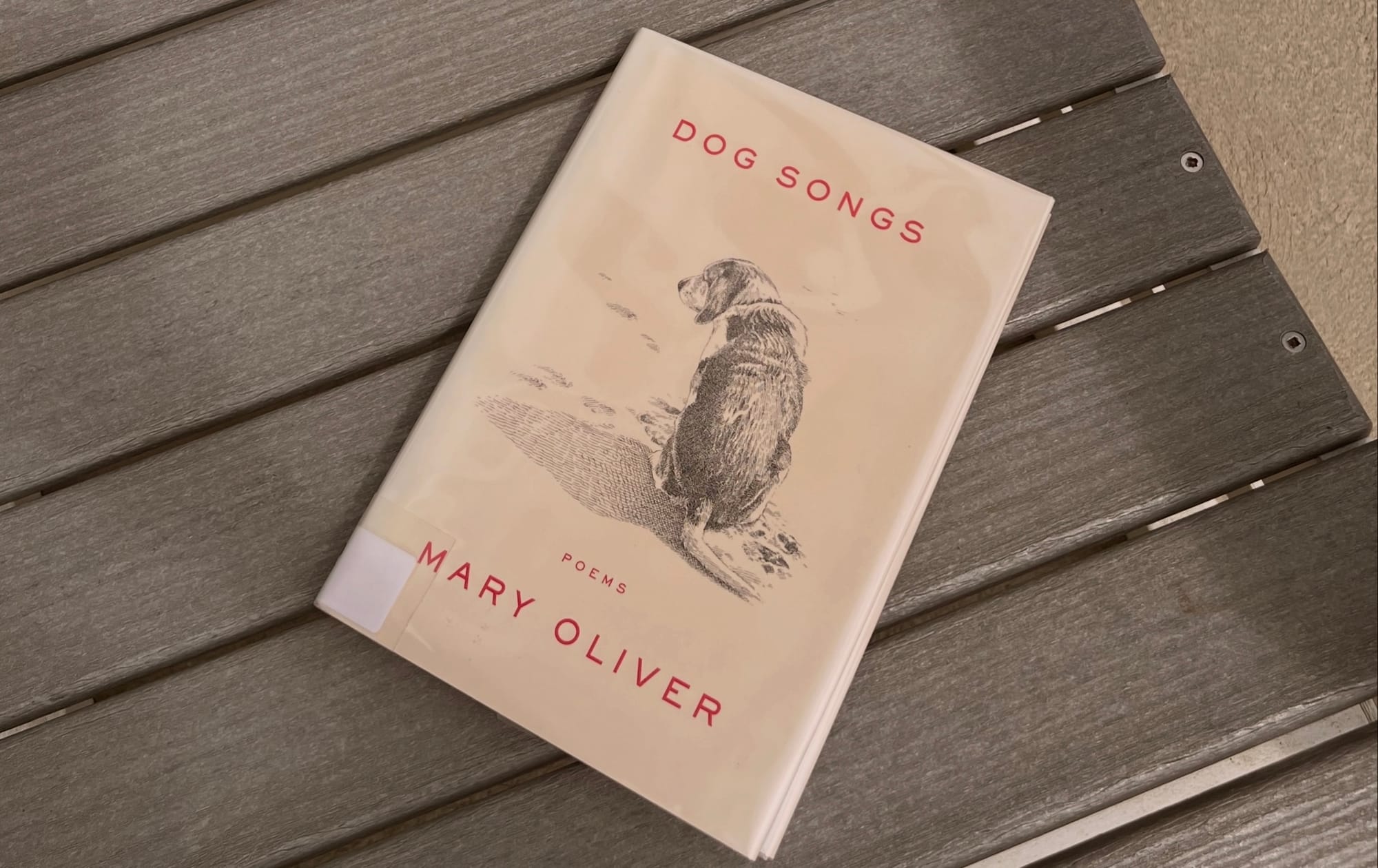

I swiftly moved through her Pulitzer-Prize winning American Primitive (1983), taking care to linger on the pages he'd dog-eared. I ventured into her selected essays via Upstream (2016). Most recently, I revisited the wondrous world of Dog Songs (2013).

Oliver's celebratory volume on the human-dog bond is luxurious and always leaves me teary-eyed. Within its pages, she offers various unique odes to the dogs of her life – "Luke," "Percy," "Bazougey," "Benjamin, Who Came From Who Knows Where" – as well as astute reflections and commentary about canine inclusivity.

Some of her pieces are spectacularly playful, while others earnestly traverse the stark heartbreak of dog loss. Both a testament to the manifold joys that our canine companions bring to our lives and a balm to the grieving dog parent, Oliver's collection, as a whole, endures by meeting dogs unleashed...in the grass or on the beach, celebrating them as they are: intensely loyal, marvelously messy, admirably exuberant, and wise.

Inspired by Oliver's wonder and curiosity, here are some highlights from Dog Songs (with analysis from yours truly) that extol canine companionship adjacent to the Roch Society's founding principles.

"How It Is With Us, And How It Is With Them"

This early poem in the collection highlights what many of us know in our bones but can rarely articulate so succinctly:

"Steadfastness, it seems,

is more about dogs than about us.

One of the reasons we love them so much.

In much of Oliver's work, there is a charge to reexamine what we lose "in our busyness." Here, she highlights the divergence of 'us' humans from 'them' (i.e., our dogs), not as a means of hierarchizing existences but as a reminder that dogs have much to teach us, the least of which being a lesson of loyalty or steadfastness.

There is a rather worn stereotype of dogs (and many other companion animals, for that matter) being charmingly 'simple' in their unwavering love, and I think Mary Oliver declares otherwise or, at the very least, prompts us to reexamine what we mean by 'simple.'

In my estimation, what Oliver gestures toward is not simplicity, but clarity. Dogs have a clarity of engagement with the world that we largely second-guess or fail to access ourselves. What Oliver poetically indicts is how we’ve overcomplicated our own capacity for presence.

In turn, the concluding line – "one of the reasons we love them so much" – is rather sobering, not just gushy sentiment. The implication is that we love them so much because we know, consciously or not, that we have indeed drifted from these qualities ourselves. Thus, in a dog's company, we’re not only comforted but gently corrected. And in that correction lies the possibility of return to this kind of steadfastness that our dogs embody so fully.

"The Poetry Teacher"

In the context of canine inclusivity, this short poem tells a story with an essential point: dogs shouldn't have to "earn" their way into our creative landscapes and workspaces.

Oliver begins by describing the beginning of her new university job, being offered a classroom all her own with a glaring stipulation: "You can't bring your dog." She pushes back, pointing out that it's all written in her contract. A tense tête-à-tête begins, and she is forced to accept a new bargain: move to a different classroom in "an old building" and only then can her dog, Ben, come along for the ride.

She eventually agreed, "kept a bowl of water in the room," and made a dog-friendly haven for her poetry students:

Ben, his pals, maybe an unknown dog

or two, all of them thirsty and happy.

They drank, they flung themselves down

among the students. The students loved

it. They wrote thirsty, happy poems.

Even though the conclusion of this poem is upbeat, maintaining this winning attitude, the vignette as a whole prompts us to ask more seriously: Why are spaces like this the exception to an exception? Why is true dog-friendliness still so rare, still something to be bargained tooth and nail?

No doubt, there’s still significant work to be done in translating this kind of poetic inclusivity into policy. Dog-friendly workplaces are still regarded as ideal but unrealistic perks rather than as a paradigm for creating a culture of vulnerability and interconnectedness. Concerning the hospitality industry, Roch is fighting to turn the tide through The Roch Standard, encouraging a renewed dialogue on accommodation vs. accessibility, tolerance vs. inclusion.

Of course, not every workplace can or should accommodate every animal, but the spirit of the poem asks us to imagine more generous structures of interspecies care, creativity, and connection.

(And hey — hit my line if you want to start a dog-friendly writer’s workshop! Why isn't that a thing??)

"The First Time Percy Came Back"

There are a lot of poems to weep over in this collection, as Oliver presents such staggeringly profound and effective eulogies for the dogs she's loved over the years that have passed away. One particularly notable piece on grief and loss is "The First Time Percy Came Back."

The first time Percy came back

he was not sailing on a cloud.

He was loping along the sand as though

he had come a great way.

Rather than looking to offer closure in the conventional sense, Oliver's poem opens a door to the soft, fuzzy-but-familiar liminal spaces between waking and dreaming. Her departed Percy comes back to visit the same beach they used to traverse routinely and gladly. He returns from a space still unknowable to her; he is both tangible yet unreachable, "as music is present yet you can't touch it."

Oliver meditates on the notion that dogs will have much to teach us in another life, too, beyond our physical reality. She gives Percy dialogue, and the conversation between the two of them is largely one-sided. Percy appears as a sage, seemingly able to read her mind: "'Yes, it's all different,' he said."

To the skeptic, this poem is just recounting how our memories are recreated in the fabulism of dreams, but for many dog-lovers (myself included), who have experienced having a soul dog or soul animal, this beautiful interlude is not so easily dismissed as pure fiction and fantasy.

"Dog Talk"

Although Dog Songs is known, first and foremost, as a collection of poems, it concludes with a single prose piece called "Dog Talk." In just a few pages, Oliver distills the overarching spirit of the book, providing a resounding ode to the unleashed dog.

The plot thread is very subtle: a nighttime routine of sorts for her dogs, Ben and Bear, as they run freely from the fields to and from home. Writing "of night and dog," Oliver ultimately fixates on the notion of wildness. She wields the term 'wildness' removed from its negative connotation of ferocity or chaos. In watching her dogs move through the world, their wildness is reframed as something sacred.

She muses about what dogs dream about and what it would be like to experience the world through their enhanced senses: "the wild, high music of smell, that we know so little about." She recognizes how dogs live in two worlds, per se, and their "galloping life" is one that beautifully intersects with ours but also greatly surpasses it in its sensorial richness.

Oliver doesn’t try to decode this distinction, this mystery in its entirety. Instead, she lets it simmer. Using the condensed metaphor of the 'house' and the 'fields,' she points to the possibility that dogs are not just domestic companions but emissaries of a way of being that is less governed by ego or anxiety, and more attuned to the natural cadences of joy, rest, and return.

In this way, the dog's “galloping life” isn’t something to outrightly tame, but something to protect and learn from, if we’re willing to slow down enough to watch, to follow, to listen. She writes:

Because of the dog's joyfulness, our own is increased. It is no small gift. It is not the least reason why we should honor as well as love the dogs of our own life, and the dog down the street, and all the dogs not yet born.

And that right there is the key takeaway. Our joy, our clarity, our ability to be here is increased in their company. It is, indeed, no small gift.